Electrical brain stimulation equipment – which can boost cognitive performance and is easy to buy online – can have bad effects, impairing brain functioning, research from scientists at Oxford University has shown.

A steady stream of reports of stimulators being able to boost brain performance, coupled with the simplicity of the devices, has led to a rise in DIY enthusiasts who cobble the equipment together themselves, or buy it assembled on the web, then zap themselves at home.

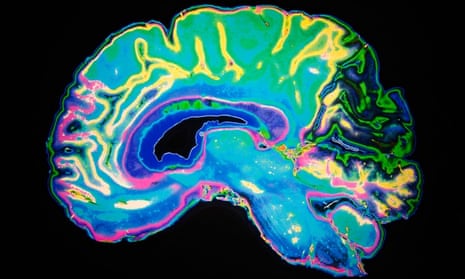

In science laboratories brain stimulators have long been used to explore cognition. The equipment uses electrodes to pass gentle electric pulses through the brain, to stimulate activity in specific regions of the organ.

Roi Cohen Kadosh, who led the study, published in the Journal of Neuroscience, said: “It’s not something people should be doing at home at this stage. I do not recommend people buy this equipment. At the moment it’s not therapy, it’s an experimental tool.”

The Oxford scientists used a technique called transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) to stimulate the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in students as they did simple sums.

The results of the test were surprising. Students who became anxious when confronted with sums became calmer and solved the problems faster than when they had sham stimulation (the stimulation itself lasted only 30 seconds of the half hour study). The shock was that the students who did not fear maths performed worse with the same stimulation.

The results showed that while brain stimulation appeared to help those who needed it most, it impaired the performance of others. Measurements of cortisol, a stress hormone, found that brain stimulation let anxious students control their anxiety, but prevented the less worried students from doing the same.

In a follow-up study the scientists found that all of the students who had brain stimulation fared worse at a completely different task – that involved spotting which way an arrow was pointing on a screen when distracting information appeared next to it.

“From these lab experiments we can see that some people will benefit and some will have an impairment,” said Cohen Kadosh. “With DIY tDCS we cannot know if it’s helping, or has no effect, or if it’s damaging.”

Nick Davis, an expert in brain stimulation based at Swansea University, said the differences in how people responded to brain stimulation were crucial to understanding if the technique should be used as a treatment to boost performance.

“Neuroscientists often ‘sell’ the benefits of their work without really talking about the drawbacks, but it’s an important thing to do. There are some real cognitive enhancements to be had with tDCS, but I also think at the moment we don’t understand it well enough to make it generally available,” he said.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion