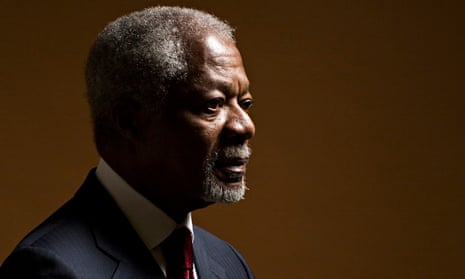

The former UN secretary general, Kofi Annan has called for the tackling of depression to be made a global priority, with mental health incorporated into a new UN Millennium Development Goal after the deadline for achieving the current goals passes in 2015.

“The failure to tackle depression undermines the fundamental human rights of millions and millions of people,” he said. “This begins with the denial of even the most basic levels of treatment and support.”

Annan said the collective failure to confront the condition, which affects almost 7% of the world’s population – 400 million people – was not a result of a lack of knowledge about treatment, but a failure to recognise the scale of the problem and put in place resources to overcome it.

“The challenge is to find the global vision and leadership to maximise the benefit for individuals and families.”

Speaking at a forum in London on Tuesday about the global depression crisis, Annan praised the World Health Organisation (WHO) for stressing the importance of good mental health, but said that even in developed countries help for people with depression often lagged badly behind help for those suffering from physical conditions. In less-developed countries, he said, support and treatment could be non-existent.

“Too often and in too many societies those with mental health [problems] face discrimination and isolation,” he added. There was a lack of resources and trained mental health providers, he said, “but we also have to deal with the social stigma and lack of community understanding associated with mental disorders. This is all the more shocking given that depression can affect all of us. There will hardly be one extended family where one member has not suffered from depression.”

The forum, organised by the Economist, brought together psychiatrists, policymakers and business leaders to discuss the global crisis of depression, which in 2010 was estimated to cost $800bn (then £520bn) a year in lost productivity and healthcare costs, a sum expected to double over the next 20 years. The WHO estimates that depression is already the leading cause of disability worldwide.

The UK health minister, Norman Lamb, welcomed Annan’s call to put mental health on the UN’s development agenda.

“Faced with the statistics, no one can underestimate the extent of the problem or the challenges that lie ahead of us,” he told the meeting. But Lamb said that in the UK and elsewhere there was an imbalance of resource allocation between mental and physical health. “Mental health always tends to lose out. That in my view has to change.”

Ahead of the meeting, Prof Simon Wessely, president of the Royal College of Psychiatrists, told the Guardian that the mental health problems of patients with serious physical conditions such as cancer, heart disease and diabetes were too often ignored. He said that in the UK, the NHS was organised in such a way that physical and mental health problems were addressed separately, despite research showing that tackling psychological issues such as depression not only improved patients’ quality of life but also improved physical outcomes.

Ideally, physical and mental issues should be addressed concurrently, he said, but the way services were delivered in separate hospitals by different professionals mitigated against this. “We have separated out the mental and physical,” he said. “The truth is that for many generations we’ve considered the physical side of illness to be more important than the mental side.”

Other key speakers at the forum included David Haslam, who chairs the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Haslam agreed that there was a tendency to organise treatment around single conditions. He said that for patients with chronic pain, heart disease and breathing difficulties, in particular, depression was often a significant factor in their lives that went untreated.

“I suspect that for a long time there was almost a naive feeling that people with long-term conditions were probably fed up with having long-term conditions, but now people are realising that it’s actually much more significant than that and needs treating very seriously.”

Wessely pointed to research at King’s College in London showing that integrating psychological therapies into diabetes services not only reduced levels of depression but also improved diabetic control. Other research, recently published in the Lancet, found that treating depression in patients with cancer improved quality of life at relatively little cost compared with the expense of cancer drugs.

“It’s a fantastically cost-effective treatment,” he said. “Of course, it doesn’t cure cancer and no one says it does, but in terms of improving the quality of life of cancer patients this was absolutely phenomenal.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion